Is Australia in recession?

Last week Federal Treasurer Josh Frydenberg made some strong statements about the Australian economy – but are we really in a recession?

But firstly, what is a ‘recession’? Economists generally agree a recession is two consecutive quarters of negative growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP), i.e. declining economic output. Currently, Australia has not yet recorded two consecutive quarters of GDP contraction, so the technical answer is ‘no’.

However, with a 0.3% fall in Australia’s GDP over the March quarter, due to the impact of the bushfires and the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic, and with the global economy still largely in shutdown, a large contraction is certain for the June quarter. Indeed, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg was quoted as saying that “Treasury were contemplating a fall in GDP of more than 20% in the June quarter. This was the economists’ version of Armageddon”. No doubt this will mark Australia’s first technical recession since 1991.

The bumpy road to recession

The March quarter GDP contraction was recorded despite a rise in net exports and grocery spending but this uplift was more than offset by the very large falls in spending on travel and other services. While this is disappointing news, it was not unexpected. Australia’s record period of expansion of 29 years was already under threat, with the Australian economy having been weak even before the full effect of the coronavirus. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), in 2019 Australia had recorded its slowest annual growth rate in more than a decade.

Moreover, the claim that Australia has gone 29 years without a recession has been subject to some conjecture along the journey, with the economy falling into a “per capita (household) recession” three times during this period. A “per capita recession” is where economic growth has been below population growth.

How long could the recession last?

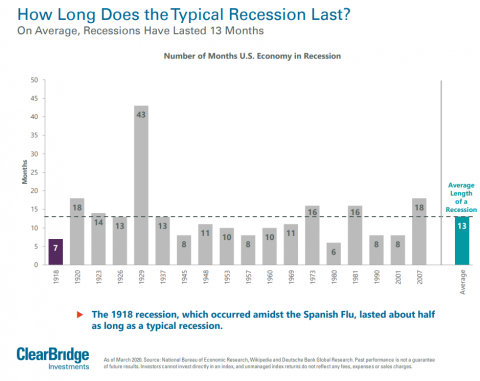

This is obviously unknowable but according to data supplied by fund manager, ClearBridge, the average US recession lasts for 13 months (see chart below.) While this is not Australian data, we believe that the US experience provides an appropriate proxy for a democratic market-based economy like ours.

Although the damage from this recession has already been as significant as any before it (except for perhaps the Great Depression), the hope is that because this has been a self-induced recession i.e. implemented to stop the spread of the virus, and not one that was triggered by a financial crisis, we could potentially achieve a V-shaped (best case) recovery with things normalising relatively quickly. Indeed, this is the apparent scenario that equity markets have currently priced in.

How can Australia recover?

As is often quoted, the sheer level of support provided by Government through the JobSeeker and JobKeeper packages, among others, as well as the actions of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), have been unprecedented. To date, it is these packages that are providing a cushion for the economy, with the intent that they provide a ‘financial bridge’ for individuals and businesses through what would otherwise be the worst of the coronavirus shut down. So while it is difficult to anticipate what the path to recovery will be, the Australian economy is well placed to fare as well as, if not better than, most others.

While the lockdown has hurt the economy, it has otherwise been relatively successful in containing coronavirus, which means that Australia may be able to resume a more normal level of social access and commercial activity in a shortened period of time. Despite our trade issues with China during the period of coronavirus to date, we maintain reasonably strong ties due to China’s strong demand for Iron Ore (noting that Brazil, the world’s other major Iron Ore supplier, is having a much more debilitating experience with coronavirus, which is anticipated to negatively impact supply)

GDP data is a much watched and very broad-based measure of economic growth – another key measure will be how well employment recovers. While JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments are providing a degree of financial bridging at the moment, the real solution will be people returning to work or otherwise absorbed back into the workforce.

Australia’s overall outlook

We believe the path to recovery, at least to a point where the economy is not unduly dependent on the emergency packages and policies, is going to be a long one – and that the real test for the economy is likely to come in the second half of 2020. The caveat to this being that a second wave of coronavirus either does not materialise or is managed to the point where we do not revert to lockdown. That being the case, a good outcome will be a slow grind out of this. The other key support for this is the obvious preparedness of the Federal and State Governments to continue to provide packages, incentives, and support for the economy to recover.

Finally, Australia is not alone. While we are in some ways fortunate to have China as a major trading partner, we will not recover on our own. Indeed, much of the rest of the world needs to share this path, as a return to normalised trading conditions leads to increased demand, hence production and employment.

As always, if you are impacted by the current economic situation or your circumstances change, please contact your Financial Adviser.